Emmanuel Mouret on his filmography of feelings: “Cinema allows you to doubt”

The interpersonal and introspective French filmmaker discusses the constructs and contexts at the heart of his cinema

Emmanuel Mouret’s films are concerned with matters of the heart, and with how we feel in ourselves and towards one another. Emerging from a Mouret film into the cinema foyer, you feel as if you’ve been enlightened — the wise truths and sympathies that his characters and their interactions espouse provide a sort of cinema therapy. It’s an experience that many of us could do with.

But none of Mouret’s films have received a UK release, which makes his oeuvre a perfect fit with this Substack’s project of spotlighting films and filmmakers that deserve a larger stage. The Institut Français in London have taken matters into their own hands, giving his latest feature, Three Friends (2024), an extended run at the Ciné Lumière. A bittersweet film about the cycles of life, of letting go, and looking back, Three Friends follows a trio of women as they navigate affairs, life changes, and each other.

Emmanuel Mouret’s films move at a different, contemplative tempo to most, their characters moving in and out of each other’s lives and minds in a way that feels naturalistic and immediate. Sitting down to watch Three Friends in the middle of a packed day at this year's International Film Festival Rotterdam, I found my breathing slowing and my mind clearing. I didn’t write a single word in my notebook.

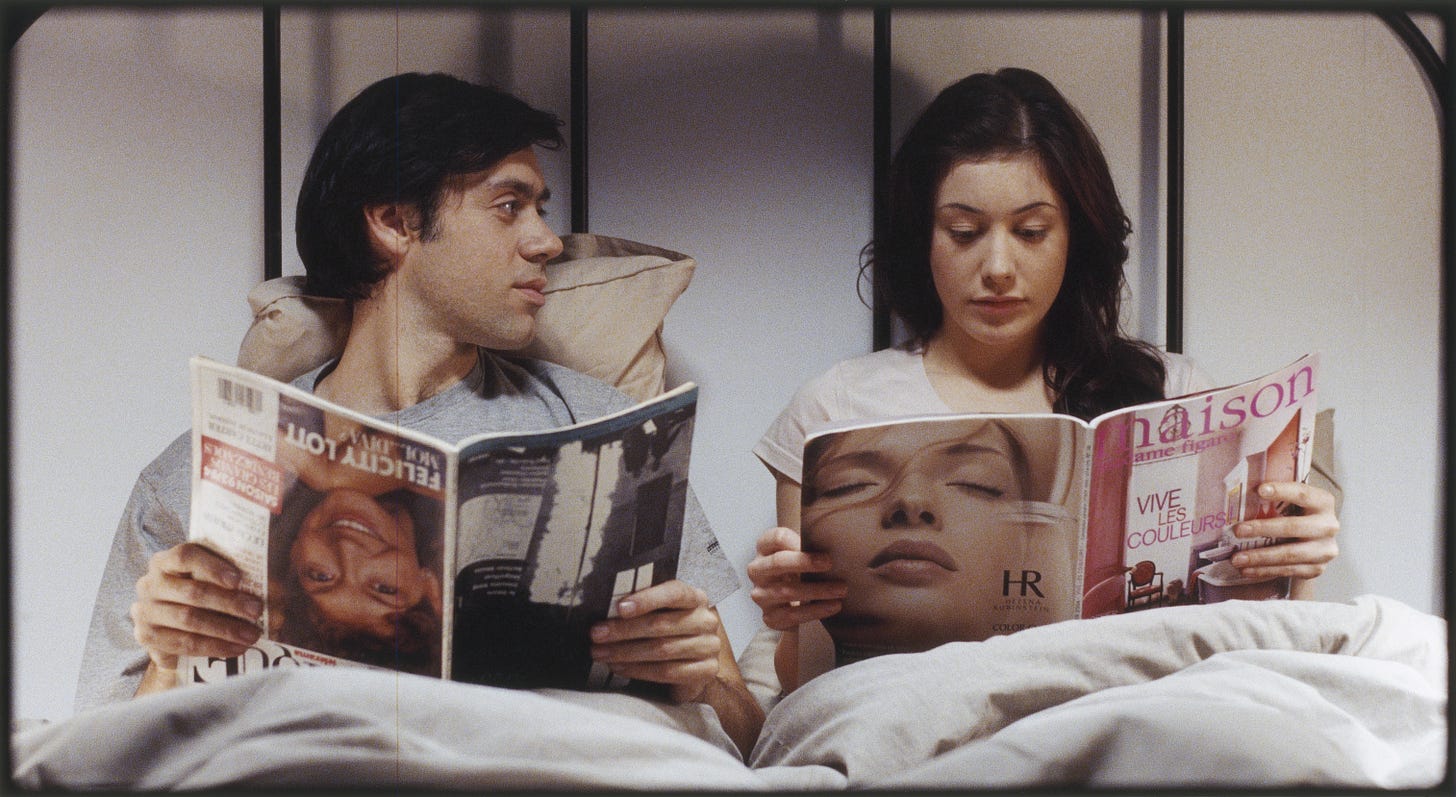

In his earlier work, Mouret was the leading man, stumbling into (and fumbling through) a series of romantic pursuits both ill-advised and inevitable. These films are delightfully charming and eminently watchable, their light touch belying resonant truths about the way we love. (American readers, 2007’s Shall We Kiss? is on Tubi, and it’s essential).

The director last starred in 2015’s Caprice and he’s stayed behind the camera since. His explorations of the heart have expanded to include a period drama and a Queer Palm nominee. His later films feel more serious — clenched somehow — but Mouret sees them as part of the same project, not as separate phases of his career — evidencing, much like his films, that we can change and remain true to ourselves.

Which came first for you, the desire to become a filmmaker or the desire to explore romance in your work?

I first wanted to become a filmmaker. Exploring romance wasn’t necessarily a purpose of mine — many others had explored it before me. But it allowed me to project myself, and to find a spot where I belonged. Love triangles and other such romantic situations are things that have always existed in cinema, and they’re emblematic.

Why romance?

Because stories of desire and feelings are important. A couple is a microcosm of human society and history as a whole. By looking at relationships between two or three people, we can question our habits and enlarge moral questions. And there’s a pleasure in the suspense that those tensions bring.

Your protagonists rarely actively seek out love, more often they stumble into it. How do you go about scripting these coincidences and chance meetings such that their progression feels natural?

Coincidences and chance encounters are only interesting if they make things more complex. In cinema, what seems truthful and believable are complications. Simplifying the situation wouldn’t be believable to the audience.

Your on-screen persona in your early films is clearly defined. As with other comic directors, we come to expect almost the same character from you across these films. How would you describe this character of yours and how did you develop him — and how close to your real-life younger self was this character?

He must be somewhat similar to myself, I suppose. I tried to make him as close to the cinema characters that I liked as a spectator, that is to say characters who are not very sure of themselves, clumsy, but at the same time candid and clever.

Your films thrive on the believable and evolving chemistry between your characters, which in your earlier films is between yourself and your co-leads. How do you foster that chemistry — what’s your process on set?

The script is the key — the actors follow its course. It’s mechanical — built like a well-engineered machine with everything in its right place. The chemistry corresponds to the mechanics of the script.

The staging and directing is precise, but not too tight, such that it leaves space for the actors.

Your films feel equally celebratory of relationships that don't work out as they are of relationships that do. You seem highly sympathetic to the changing affections of your characters.

What I like about the outcomes of my stories, in regard to my characters’ desires, is that they sometimes end in failure, but they’re happy failures. These characters don’t necessarily succeed where they want to succeed, but they find success and happiness nonetheless, often in unexpected places.

The other thing I notice is that they’re torn between respecting their existing relationships — between being good, moral people — and being honest with their own feelings and desires. This conflict of honesty, this decision whether to follow your commitments or your own self-centered goals, is something that I find interesting.

Caprice feels a final statement of your initial screwball style. Was it envisioned as such?

No, not at all. Something happened. After Caprice, my producer wanted me to make a film in which I don't star — a period film, Lady J (2018). It was very well received in France. There was no active intent to move to something else, it just happened that way.

What led you to move on from casting yourself in the lead roles of your films?

I actually never cast myself of my own desire — my producers were the ones who pushed for me to play the lead. Caprice didn’t do so well, Lady J did, and that was a good enough reason to not have me play the lead any longer.

Do you view your later films as a separate phase of your career, or as an extension of the themes and styles you explored in your earlier, more straightforwardly comedic works?

I don’t think my films have changed too much, other than the fact that I’ve stopped acting in them. I probably don’t see it as clearly as the audience does. When I act in my own films, I can’t help but try to make it a little funny so as to not be boring.

What is shifting and changing in your perception and perspective on the world as you get older, and are these factors shaping or reshaping how you approach filmmaking?

That’s a difficult question. As you continue to make films, you become more and more aware of the things you can influence and change here and there. So it requires more and more focus to properly make them. The one real change is that, since I stopped acting, I can focus fully on the staging and directing, and I can ask more complicated things of my actors. That’s why, in the films that I don’t appear in, there are more long take sequences, for example.

I'm curious as to your thoughts on the international reception of cinema that takes romance as its subject. To some, romantic cinema is vital, but to others it's considered slight or trivial. I'm glad there's the Cabourg Film Festival in France, but I don't think there are many instances where romantic cinema is taken seriously as a major mode.

Personally, I don't put a genre on my films, but I know that my films are perceived as rather light. I’d describe them as melancholy comedies. But it's true that from the moment that there's a lightness in tone, you’re suspected of being light in what your film offers in general. To offer something that’s deemed essential, you have to make a film that is heavier.

What does making films do for you as a person? I presume you find it an enriching process.

Making a film begins with a gesture, a thought. The interest in making a film is to see what that thought will look like when developed. My whole day-to-day is built around making films.

What do you hope that your films bring to the lives and hearts of the people who watch them?

I take up this idea of Ettore Scola’s, who said that in the current world, television, internet, newspapers, and radio tell us what to think, and that cinema allows you to doubt — it’s a space where you can doubt. In cinema, you can suspend hasty judgement and find something beautiful, despite the cruelty of things.

Three Friends screens exclusively at the Institut Français until the 14th June. You can book tickets here.

With many thanks to Diane Gabrysiak and Méthode Lacour-Cartau for translating, to Emmanuel Mouret for his generosity with his time, and to the team at the Institut Français for facilitating this conversation.