Tetsuichiro Tsuta talks 'Black Ox': “Humanity’s extinction is not the end of the world”

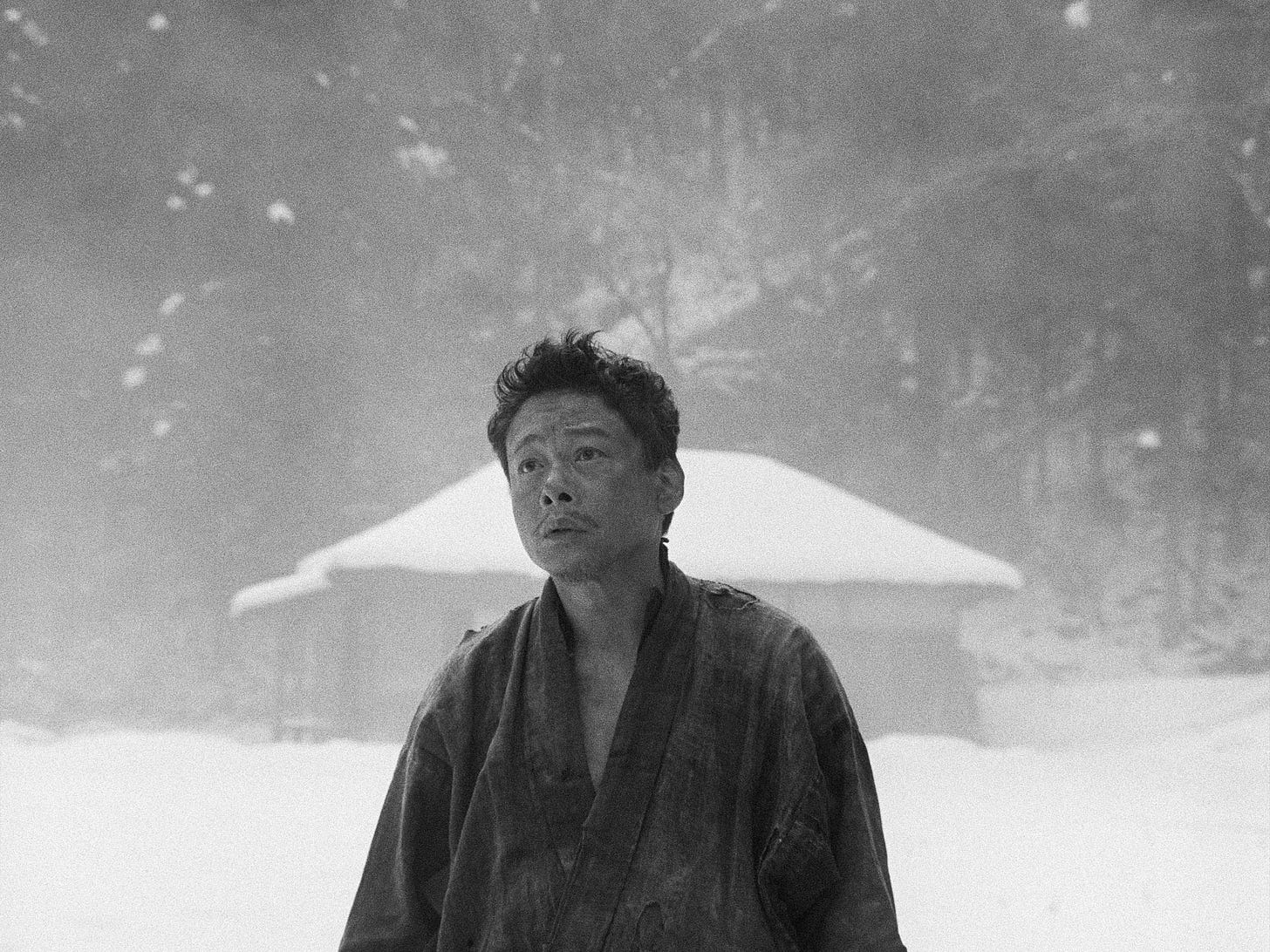

Tokyo International Film Festival 2024 is surely only the first stop for this gorgeous Lee Kang-sheng-starring fable

The Tokyo International Film Festival is having quite a year.

When I reached out to select filmmakers from this year’s programme to conduct lengthy Zoom interviews about their new works, I was unaware that the festival had been reaching out also, bringing Western journalists from key outlets to this year's festival in person.

It's an exciting moment to be a fan of Japanese cinema. So much in 2024 has pointed to a shift in the way that we’re approaching it internationally, and Japanese cinema itself is beginning to look further outwards too, to fascinating, form-shattering results. The world is beginning to pay attention to what has long been an under-discussed scene, and we may be on the cusp of a new wave.

One film at Tokyo IFF this year that I especially hope journalists and distributors took note of is Tetsuichiro Tsuta's engrossing slow drama in ten chapters, Black Ox.

Its opening moments are certainly enough to jolt you out of your jet lag. Across some dimly-lit mountains, an orange glow can be seen. Is this early morning or perhaps late evening? A sunrise, or a sunset? The ambience sits at a light buzz as we linger on this image, a bird is heard pleasantly chirping. And then, a sudden cut to a loud and violent fire, captured in vivid 70mm colour. When the title card fades from its grey block background, we pan down to a monochrome world made post-apocalyptic through montage.

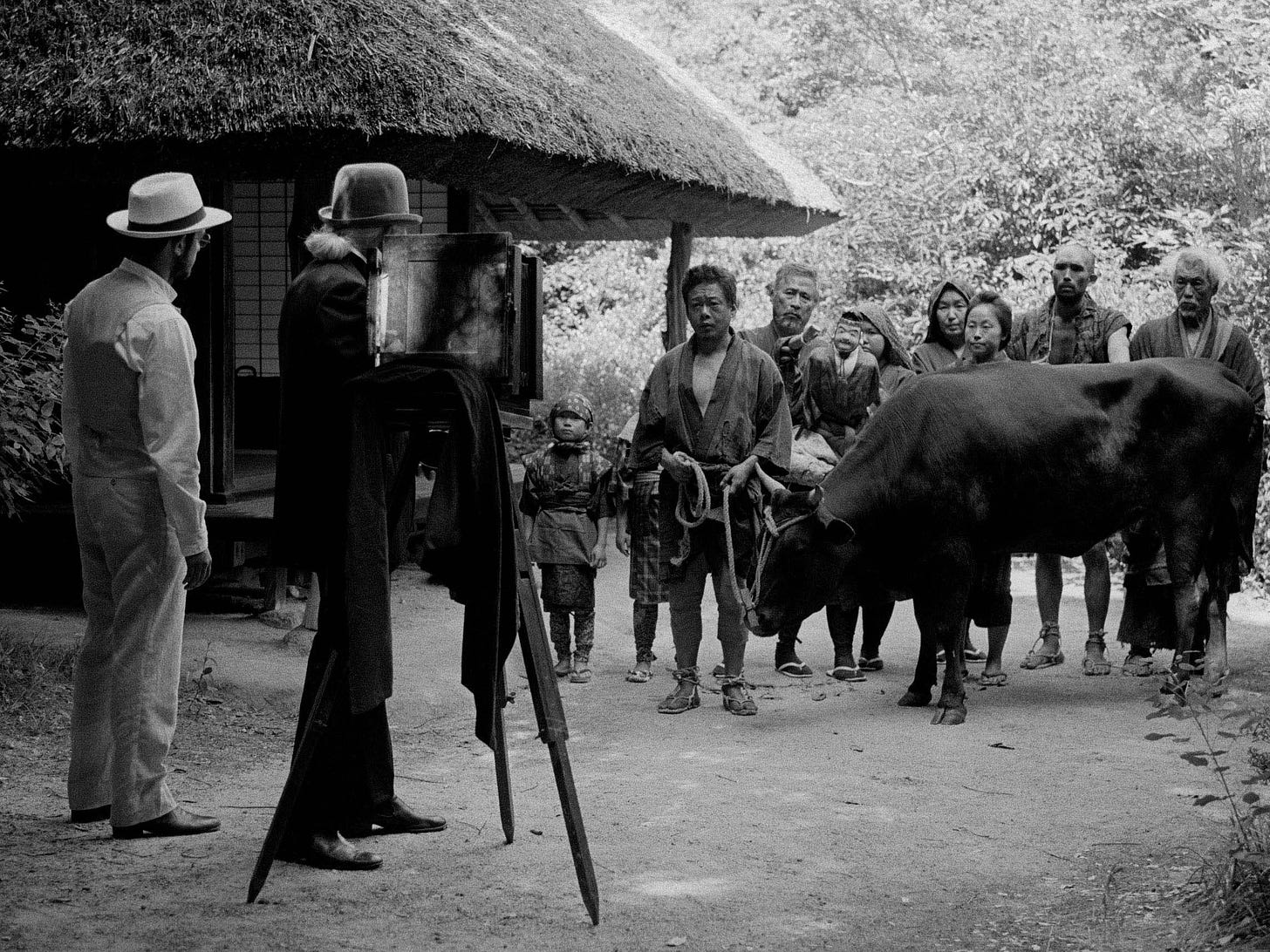

'Spiritual experience' is a buzzword phrase that's often used hyperbolically, but it's appropriate phrasing here. Tsuta's film adapts the 'Ten Oxherding Pictures’, ink brush paintings that explicate the Zen Buddhist path to enlightenment through ten interactions with an ox. His film rendition is a meditative masterpiece in the slow cinema sense, expertly crafted, but with some radical subversions up its sleeve. It’s a quiet piece that builds to a hum, then a roar.

Black Ox is exactly the kind of film that this Substack is about. It demands distribution, and I'm confident that there's an international audience ready to be beguiled by it. Our conversation is also exemplary of the directions that I love my interviews with filmmakers to take. Over the course of a richly rewarding hour, Tsuta-san and I share in our cinephilia, discuss the impact of 35 and 70mm film, and ponder where the future might take us.

This is my first encounter with your work. I'll definitely be seeking out your other films, because I think this film is extraordinary. To start us off: How would you define your style of filmmaking or your filmmaking philosophy?

Most of all, it was important that everything was shot on film. I focus a visual beauty in my work that shows up better when shooting on film.

It wasn’t an option to shoot this film on digital. For Black Ox, I used 35mm black-and-white and 70mm colour. It’s actually the first time a Japanese feature has used 70mm colour film, and it has long been my dream to use it.

The sharp texture that each lends this feature is incredible. I'd love to hear more about your decision to utilise them both within the same film.

The decision to use 35mm black-and-white was because our main protagonist in this film is an ox. Shooting on film captures the inky blackness of the animal beautifully. At the time of the shoot, there was no 70mm black-and-white available to us, so this was the best option that we had. After Oppenheimer, 70mm black-and-white became available.

The other reason is that this film is a historical period drama. I wanted to represent the Ten Oxherding Pictures, and 35mm black-and-white worked better to influence the audience’s imagination.

I chose 70mm colour for the film’s final segment because I wanted to create a completely different world from what preceded it. It looks like the future and the past simultaneously, and also an alternate world where humankind is absent. It’s completely different and larger scale, so 70mm colour was the right choice.

As you said, this film is inspired by, and structured after, the Ten Oxherding Pictures. Could you tell me about your first encounter with them?

My first encounter with them was actually on the internet. I wanted to shoot a film centering oxen or cows, and I was searching for something that could be the core of that film. I came across the Ten Oxherding Pictures, and from there I started looking into literature and books related to that concept. The philosophy at the heart of it is the process of reaching nothingness, It relates to what it is to be human, and to life itself. It’s an explanation for the whole world. I felt that there was a universal quality to it, and that it inspires the imagination towards new understandings.

Dividing into ten pictures isn’t really a structure for normal filmmaking, but I thought it could be interesting to apply it to my film. It was my curiosity, first and foremost, that led me to make a film based off of this. It felt like an interesting challenge.

Well the results are extraordinary.

I want to go back to your use of black and white. The stark contrast of the whites and the blacks in these monochrome scenes make the film feel like a film out of time, in a sense.

It feels decades old rather than necessarily a film made in the 2020s. Was it the intent to make a film that doesn't necessarily feel modern but perhaps feels timeless? Because you succeed in that brilliantly.

The decision to use 35mm black-and-white was partially inspired by classic Japanese films. Ozu, Kurosawa, of course, but most of all Mizoguchi’s film Ugetsu.

It wasn’t my intention to create something that looked like an ‘old’ film, but I wanted to prove the potential of black-and-white film for contemporary audiences, that it’s actually fun to watch.

Thinking on cinephilia further, you have Lee Kang-sheng in this film in the lead human role. He’s best known of course for his collaborations with Tsai Ming-liang, to which he brings an incredible level of vulnerability, emotional and physical. You ask a similar vulnerability and nakedness of him in your film. This is your first time working with Lee, how did you develop that trust in your working relationship?

When we were thinking about the casting for the protagonist, Japanese producer Shozo Ichiyama suggested Lee Kang-sheng. Of course, I was familiar with his work, but I hadn’t considered him for the main protagonist role. It was thanks to Ichiyama and our Taiwanese producer. They approached Lee Kang-sheng for this part.

I went to their offices in Taipei to meet him. I explained the concept, my thoughts behind it, and the character. I also showed demo reels for the film. And he accepted the offer.

I find it interesting that you’ve cast an international actor in this, in some ways, quite Japanese film. In an early intertitle, you define the setting of the film as being ‘a certain island country’. I’d love to hear more about your decision to be specific and yet non-specific with the national backdrop of this film, and whether you feel it is a ‘Japanese film’, or whether you feel it is an international film by Japanese talent.

I didn’t have the intention to make this film look like a Japanese film per se. I intentionally left the location and time period somewhat ambiguous. In actuality, it’s sometime in the Meiji period, but the film doesn’t make this explicit. As it’s spoken in Japanese, I guess that would categorise at as a Japanese film.

Lee’s character was meant to be ethnically ambiguous. He could be of a Japanese mountain tribe, or equally someone from Southeast Asia. I cast international actors to make the setting more mysterious and ambiguous. I think Lee’s presence perfectly matches what I was looking for.

Your other lead actor is of course an animal. How did that work logistically? Was it a challenge during production?

We actually borrowed cows that were intended for meat production, Wagyu. Three months before the shoot, we started training.

Back in the day, we used to cultivate farms using cows and oxen. Nowadays, few people do that, but there is one person who still farms this way, in Iwate. So we hired that guy. He trained and prepared all the cows and crew for the cultivating scenes.

Tell me about pre-production. What strikes me most about Black Ox is that it has this beautiful sense of seamlessly shifting from location to location. How much of that was storyboarded or mentally storyboarded?

This film is shot one scene to one cut. For each location, we captured only one shot.

Originally, I was planning to do only ten cuts, because of the text ‘Ten Oxherding Pictures’, but it was a bit difficult. If we were to do that it would have been one take for ten minutes. We decided to distribute it a bit more. Ultimately, the film turned out to be 110 cuts. Rather than creating montage, I wanted to split the cuts according to the scenes. The reason it appears quite seamless is because of the editing. And also the cinematographer, [Yutaku Aoki], their skill at creating camera movement that appears smooth and seamless.

Where did you shoot this film?

Most of the film was shot in Tokushima, in Shikoku. And we also went to different locations within Shikoku, such as Kagawa, Kochi, and Ehime. Tokushima is where I grew up.

Tell me about the environmentalism of the film. You're shooting in nature throughout, and you open and close with these sudden flashes of natural destruction. These are evocative images, and I'd love to hear about the environmentalism that appears to underpin them.

This film sets out to question how we can regain the relationship between nature and humans. The story of the film itself is of how a primitive mountain tribe is affected by modernisation, and how they survive it.

As human beings, we were once connected and integrated with nature, but, because of modernisation, this connection has been disrupted.

We want to regain that relationship, but we can’t. We can’t go back to our primitive lives, modernisation is irreversible. The question of how we can rebuild this connection from where we now find ourselves is the theme of this film, and also the central question in my own life.

I want to ask about the score by the late Ryuichi Sakamoto. Tell me about working with him. I love how sparsely you use his music throughout the film.

I decided to work with Ryuichi Sakamoto because he was an artist with an acute awareness of environmental issues. He was involved in activism, not just music, and I have a lot of respect for him.

At the time that I was shooting the demo reel for this film, there was a video competition for Ryuichi Sakamoto’s new album. The idea was to create a video using Sakamoto’s music. I applied to that competition using this demo reel.

Sakamoto himself was on the judging panel for the competition. I heard back that our demo clip reminded him of the films of Béla Tarr, one of my favourite filmmakers. It got me thinking that we could work together on the film itself. We reached out to him through producer Eric Nyari, and Sakamoto accepted.

The way that you utilise Sakamoto’s score in Black Ox reminds me of another film, Masakazu Kaneko's The Albino's Trees, which sparingly used original music by Eiko Ishibashi. Are you familiar with it?

I have a lot of respect for Eiko Ishibashi, her music of course appearing not only in The Albino’s Trees, but also Evil Does Not Exist by Hamaguchi. Her ambient approach to environmental sound is quite similar to our approach and structure in this film.

As for Masakazu Kaneko, we know each other personally. Our interests in cinema are alike in the way that we deal with environmental themes.

In regard to the way in which we use Ryuichi Sakamoto’s music, the main sound in this film is environmental sound. We use his music here as an overture and as an end roll. It’s sort of like wrapping the film. Sakamoto-san’s music is wrapping around my film, that’s the image that I got from the music he composed.

I recognised a parallel between your filmmaking and Kaneko's, so that's lovely to hear.

Talking more on the sound design, it's wonderfully arresting. The first ten minutes of the film especially feel quite oppressive. Could you tell me how you crafted a soundscape to match the landscape and Sakamoto’s music and brought all these elements together in harmony?

The sound design was a collaboration between a Taiwanese sound designer and a Japanese sound designer. The Japanese sound designer, Izumi Matsuno, is actually the sound mixer for Evil Does Not Exist. Aurally, I wanted to pursue not only the realistic, but also something that could heighten the atmosphere.

For the first shot, I wanted to make it a bit creepy, whilst solely utilising the normal environmental sound that we captured. It’s just the sound of the wind. Without any instruments or any sort of modern technology, we used recorded natural sound to create this atmosphere.

It's an unusual comparison perhaps, but that opening sequence reminds me of David Lynch's Eraserhead in terms of atmosphere.

I like Eraserhead too, but that wasn’t intentional. I was inspired more by Béla Tarr and Andrei Tarkovsky.

I can see those influences in the film.

Speaking on internationalism, now that we're talking about international directors, this film will definitely travel. I think Black Ox has a great life ahead of it at further festivals and hopefully Western distribution.

Have you made this film more for a domestic audience, or have you made it with an international audience in mind?

I had thought it was more for an international audience. For my personal ambitions, I wanted to send this film to A-tier film festivals, especially the big three. But after making the film, I found that its central philosophy, the zen and the seeing the worth within nothingness, is intrinsically Asian, closest to Buddhist philosophy.

I’m concerned as to how difficult it will be for Western European audiences to connect with and understand this more Asian way of looking at nothingness. So now, with how the film has turned out, I guess it’s more for an Asian audience.

Your film brought to mind the 2022 Icelandic/Danish film Godland. I don’t know if you’ve seen it, but it’s a cousin to this film, I feel, as it explores Western philosophy and religion through a natural landscape.

I’ve seen it too. The central idea in that film, of a photographer disputing religion and going to places of cultivation, is quite similar. I empathise with the philosophy there of human beings trying to achieve something within vast nature.

The photographic technique used in that film is the same as in our film. It’s called the collodion process. I found that interesting.

As a final question, what do you hope to instil or inspire in the audiences of this film, whether that’s a feeling, a message, or an outlook?

It’s not that I want to instil something in the audience, but I do want audiences to sit with and experience the film, and to feel that they watched something extraordinary.

The film is about how we rebuild our relationship with nature. Human beings are going to go extinct in the future, it’s been said that mammals typically go extinct within one million years. But I believe that, even after human beings, nature will become humanised in some way. I can’t explain specifically how it’s going to be humanised, but whether it’s in DNA or in some spiritual aspect, nature will become more human.

The final scene of the film represents a paradise of sorts for the ox. From a human perspective, it looks like a dystopian world. I believe that even after humans go extinct, it’s not the end of the world. It’s not something depressing, it’s the circle of life, and something similar to human beings, new life, is going to be born within this vast nature.

It’s not something that I want to tell the audience. It’s something that I want them to experience for themselves, that way of nature.

With thanks to ALFAZBET for facilitating, Tetsuichiro Tsuta for his generosity with his time and his thoughts, and for his extraordinary film, and to Kanako Fujita for interpreting.